Back in the glory days of my gaming career, when six hour sessions of D&D were a regular occurrence, and not a rare celebration, the story that developed was as much a surprise to the DM as it was to the players. Sure, the DM had read or written a module, but there was no telling how the players would approach the situation, and how they would direct the action. Those games included a third party that exerted just as much influence on the direction of the game as the DM and the players. That third player was the much loved and much vilified dice.

A concrete example: Early in The Long Campaign, the villains the characters faced had a nasty habit of getting away at the end of the tale, and returning a week later to wreak vengeance. This wasn’t by design, it was just a happenstance of the circumstances and effective dice rolls on those disengagement checks. After a string of ambushes at inopportune moments, the players started looking for way to cut off escape before engaging combat. They started cutting down every foe that cut and run, just as a means of avoiding trouble down the road.

They weren’t a particularly bloodthirsty group of players. They hid from, snuck around, bluffed through, or bribed their way past many potential combats, but once the gloves came off they didn’t stop swinging until every enemy was dead or dying. Again, this wasn’t a conscious decision on anyone’s part; it just sort of…happened.

We didn’t know it at the time, but what we were doing was an exploration of a different kind. We didn’t write stories or prepare stories, we set up a few avatars, nudged them a bit this way and that, but at the end of the day all of our choices and all of the die rolls combined to form a story that no one could have predicted at the outset. No one planned for the polymorphed wizard’s cure to leave him with frog eyes. No one planned for the thief to wind up with a 19 Dexterity despite hobbling about on a peg-leg. No one planned for the fighter to be a reckless miser willing to charge into any fight if he caught even a glimpse of gold. These were all the result of fortuitous die-rolls, but all played a major role in the game.

We didn’t so much create stories as discover them through play.

Although not nearly as frequent or colorful, we found the same sort of ‘revealed story’ in a number of hex-and-counter wargames. We remember the game of Ogre that saw the behemoth meet its victory condition in two turns only to blow all of its tank treads on the next turn, unable to do anything while it was chewed to pieces by long range artillery. We remember that last German defender in the blockhouse singlehandedly save the left flank of the board from a Soviet onslaught in ASL. Our games of Dawn Patrol always started with a dice-off for the one Sopwith counter that always survived the game. (Which version of the biplane it was escapes me now, but it was a quirky suboptimal plane.) After a while, every scenario turned into “Kill Snoopy” for the German players. We didn’t decide that counter was nigh indestructible and give it stats to ensure that, something in the universe decided that, and we just ran with it.

|

| This same process happened to tabletop RPGs. Source. |

When we started going to conventions in the early to mid 1990s, we found that most tables took a different approach. Players had prepared character arcs and full blown backstories – even before they’d rolled their first initiative. Adventures followed pre-set chapters and story lines. All of this entertainment was pre-built. You didn’t discover anything new, you just unwrapped a story already prepared for you. It was a bland and sterile way to play, and it his us just as college, girls, and so many other pursuits provided more stimulating diversions than running along trails blazed by others in tabletop RPGs.

Apparently wargames are undergoing the same sort of process.

Over on the twitbox, no less than Lewis Pulsipher himself, designer of such great wargames as DragonRage and Britannia, lamented the dearth of hex and counter wargames at GenCon 2016.

Didn’t notice a single hex-and-counter wargame at the vendors at GenCon. Lots at WBC, of course. (Can’t remember seeing hex ANYthing at GC).— Lewis Pulsipher (@lewpuls) August 12, 2016

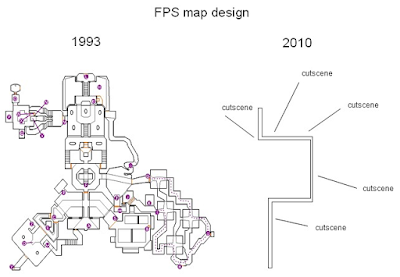

Through the course of that slow-burn conversation, we gradually approached the idea that pre-packaged stories dominate the RPG market today. For whatever reason, pretty hallways sell better than pretty sandboxes. As grubby little sandboxes, hex-and-counter wargames just can’t provide the same sense of ‘tell me a story but let me pretend to be participating in the telling’ that RPGs do. The very nature of most hex-and-counter wargames precludes set path routes. Players expect a level of freedom and decision in deployment, tactics, or timing. Wargames that limit those aspects in an effort to force players down a ‘pretty hallway’ wind up feeling more like Choose Your Own Adventure Books with a lot more fiddle bits than pages.

As a historical simulation, one would expect the player’s choices to be somewhat limited in scope. Supply, terrain, and ‘the army you have’, are all predicated on the facts of the historical encounter. And yet, players still have the option of trying a new strategy. They commit reserves earlier, attack cities from a different direction, or force a crossing farther upstream where the river is wider, but defenders lighter. Every one of these decisions can allow the tabletop general to discover a new story, rather than simply repeat the original story as recorded in the history books.

And yet, I begin to wonder if the hex-and-counter wargaming hobby isn’t following in the footsteps of the RPG hobby. Eager to write games that accurate recreate historical events, are designers writing more ‘pretty hallways’ these days? My readings suggest this is so, but my own pushing-cardboard tims is too limited to come to any hard and fast conclusions.

My own experience with Khyber Rifles has not been encouraging. It features a card driven activation system that provides a very historical feel and pace to the game, but binds players hands so tightly that any given turn provides one clear choice: do this or waste the turn. It’s great for illustrating the challenges facing the historic commanders. It’s great for providing historical reality. It’s lousy for providing interesting tactical choices. I need a few more games under my belt to make certain, but at this point it doesn’t look good for Decision Games.

The upshot of this concern is that finding more data to support my contention that even wargames are moving towards a ‘pretty hallway’ model will require finding, buying, and playing more wargames. And that’s just the kind of tactical choice that this old grognard likes to be forced into.