Last week I did a partial review of an interesting experiment in tabletop D&D. After reading through the basic theory of using Fortean weirdness to D&D to help recapture some of the magic lost by making literally everything magic, I gave the product a solid recommendation. The concept is a strong one, and Neven has given both the rules and application a considerable amount of thought.

Last week I did a partial review of an interesting experiment in tabletop D&D. After reading through the basic theory of using Fortean weirdness to D&D to help recapture some of the magic lost by making literally everything magic, I gave the product a solid recommendation. The concept is a strong one, and Neven has given both the rules and application a considerable amount of thought.

After reading through the three short adventures, I have to scale my recommendation back considerably. There isn’t enough meat to the rules and theory to justify the pricetag, and the adventures and short fiction don’t make up for the difference.

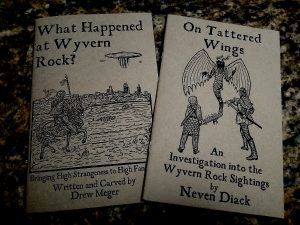

To be clear, What Happened at Wyvern Rock?, is the theory and three short…let’s call them encounters. On Tattered Wings is a collection of vignettes, and unlike the companion volume, wears its fiction leanings on its sleeve. It’s not really a story so much as a sampling of NPCs can recall encounters with Fortean weirdness, how they react, and how they struggle to make sense of new oddities in a world filled with old ones. They are useful examples of how DMs can introduce cryptids such as little gray men and mothmen into their games. They are also useful examples of why cryptids don’t really work in a world where everything is magic – in a world where nothing makes sense, the things that don’t make sense don’t fail to fit in, they are just one more flavor of, “who cares, shove that in there, too.” They are well written, and remind me a lot of the collections of encounters you’ll find in more modern day Fortean collections. As such, it makes for a useful gaming aid and the raw ore from which a good DM could take inspiration.

To be clear, What Happened at Wyvern Rock?, is the theory and three short…let’s call them encounters. On Tattered Wings is a collection of vignettes, and unlike the companion volume, wears its fiction leanings on its sleeve. It’s not really a story so much as a sampling of NPCs can recall encounters with Fortean weirdness, how they react, and how they struggle to make sense of new oddities in a world filled with old ones. They are useful examples of how DMs can introduce cryptids such as little gray men and mothmen into their games. They are also useful examples of why cryptids don’t really work in a world where everything is magic – in a world where nothing makes sense, the things that don’t make sense don’t fail to fit in, they are just one more flavor of, “who cares, shove that in there, too.” They are well written, and remind me a lot of the collections of encounters you’ll find in more modern day Fortean collections. As such, it makes for a useful gaming aid and the raw ore from which a good DM could take inspiration.

Think of it as a shotglass full of Appendix N.

Better yet, just go read Three Hearts and Three Lions, or maybe The King of Elfland’s Daughter, for a more useful reminder of how elves can be so much more than just a human with funny ears that likes to talk to the tress.

Which brings us to the three short stories included in What Happened at Wyvern Rock?

My criteria on adventure reviews is similar to that of Bryce over at tenfootpole.org. Use at the table is the point, and the metric by which I judge.

My criteria on adventure reviews is similar to that of Bryce over at tenfootpole.org. Use at the table is the point, and the metric by which I judge.

Let’s get the canary in the coal mine out of the way first. Every female NPC is some combination of smart, brave, loyal, and kind. With only rare exceptions, every male NPC is some combination of stupid, craven, untrustworthy, and cruel. Players who have any pattern recognition skills will quickly deduce that the best way to improve the odds of survival are to shank any male NPC that comes around and do exactly what the nearest Mary Sue suggests. It’s the quiet sound of a calliope in the distance reminding you that clown world will not rest – it is always waiting in the shadows, ready to turn everything on its head for no reason whatsoever. It is easily corrected at the table, but it remains a red flag of caution, and one that bears out upon further reading.

Likewise, the NPC races used are completely random and without purpose. Nothing serves to distinguish an elf from a halfling from a half-orc from a human. It’s all set dressing as meaningless as what species of trees are in the woods that surround the crashed UFO. All it does is remind the reader that magic has become so mundane and the kitchen-sink assumptions of the game so pervasive that whole new rulesets – the one I’m reviewing right now, for example – have to be built and bolted on to the game in order to try and recapture the magic that was lost when the tabletop RPG culture embraced the stone soup model of D&D.

Stone soup, for those of you who don’t know, is an old hobo tradition whereby everyone throws whatever ingredients they have into a pot. Got one potato? A couple carrots? A bit of cooked steak or a chicken leg? Chuck it into the pot, and we all share what comes out. The results is predictably a flavorless mashup, with each pot tasting more or less exactly like the one that came before.

Nowadays, every campaign is Forgotten Realms.

The core assumption that ‘everything in the books is in the game’ has made nearly every table and every popular supplement a flavorless mashup of the same two dozen ingredients. That is the whole reason Wyvern Rock feels so fresh and new – it is an escape from the stone soup. Somebody chucked a slab of salmon into the pot, and rather than taste like a nice fish stew, you just get the usual bland gruel with a hint of what might have been, with only a little more thought and planning.

And then, the adventures themselves aren’t so much adventures as they are stories written in the modern D&D skin-suit style. A place, an NPC list, a series of unusual events, and an explanation of how the NPCs react to those events. PCs not required. You could probably turn them into a D&D adventure if you were willing to put a considerable amount of work into the process. Neven gives little help in that regard. No thought was put into how to use them at the table. They are stories, not adventures. Stories crafted in an odd manner and with an usual structure to them, but stories nonetheless.

The three tales consist of:

- a swarm attack on a small, isolated homestead.

- an encounter with a woman who is more than she seems and more than she knows

- a string of linked encounters that grow increasingly more obviously little gray men

The first is combat heavy, the second exclusively role-playing, and the third…it could go either way depending on how the DM wants to run his game-train. They can be mined for ideas, but as a gaming aid, they suffer.

After the impressive lead-up of the wild and wooly cryptid theory of the first part of the book, it is disappointing that the practical application should step so hard on so many rakes.

To be perfectly fair, this is largely a style preference. Neven has gone all-in on storytelling gaming wearing D&D patches for street cred, and I am a hard core D&D player. I need adventures that can be run at the table. My worlds are heavy on mundane and boring old humans doing the grunt work of growing crops, praying to the gods, and fighting for their kings. The rare elf or dwarf really mean something more than “has pointy ears” or “has a beard”. The bits of the world that are strange and unknowable are tucked into out of the way places where most mortals fear to tread. They are not slathered all over every farmstead and city pub. So when the players march their characters down into dank holes, they know that everything is strange and Fortean, and it feels that way because so little up in the fresh air is strange and Fortean.

Thinking on it, one of the best uses of this product would be to start with one of TSR’s old green splatbooks – Robin Hood or The Crusades – and then inject this X-Files goodness straight into their veins after three or four sessions of haring off around Sherwood or chasing Mussulmen back into the desert. That would really make the best parts of this supplement sing.