It’s very hard to break out of forty years of bad practices.

It’s very hard to break out of forty years of bad practices.

Especially when everyone around you is convinced that they can make the bad practices work if they just buy one more supplement, maybe one more Gygax copypasta ruleset, or one more setting book. Especially when the guys telling you how to get right, fly straight, and play D&D the way it was intended rather than help paper over the glaring weaknesses in your play.

Those of us still toiling in the RPG fields, still struggling to save normies from conventional play and the string of failed campaigns that inevitable result from it, have been at it for five years now. Long enough that the principles for which we advocate have entered mainstream discussion. Long enough to have won every debate. Long enough that our ‘stop buying useless crap and just play the game as it was meant to be played” to have annoyed every peddler of useless RPG advice. Given our limited numbers and silent treatment from the guys whose incomes we threaten, there are still countless souls awaiting news of the resurrection of the hobby. The work of reaching those lost players is long and arduous, but not without its reward. With every new campaign adopting a rightful order, the hobby improves just that little bit more.

And so, with that in mind, let’s re-state the simple process by which campaigns can begin to take on a life of their own:

“[it is] best to use 1 actual day = 1 game day when no play is happening”. AD&D DMG, page 37

People still struggle with simple statement this because they think that – like the solutions peddled on DriveThruRPG – it doesn’t really change anything. You won’t have to recalibrate your expectations and play style because none of the solutions you’ve ever paid money for made a difference, so why would this? One of the chief difficulties of making this one little change is that players can no longer sit back and let the DM do all the heavy lifting. They have to start thinking about the campaign. They have real, actual problems to face, and more agency to determine the solutions to those problems than they’ve had in forty years.

Often, when confronted with the simplest of ramifications and challenges newcomers to this style of play will have their brains simply lock up. They cannot conceive of a situation where they need a solution that the DM didn’t already create and expect them to implement. They cannot imagine that changing one aspect of the game will have actual impact and meaning, and force them to change how they approach other aspects of the game.

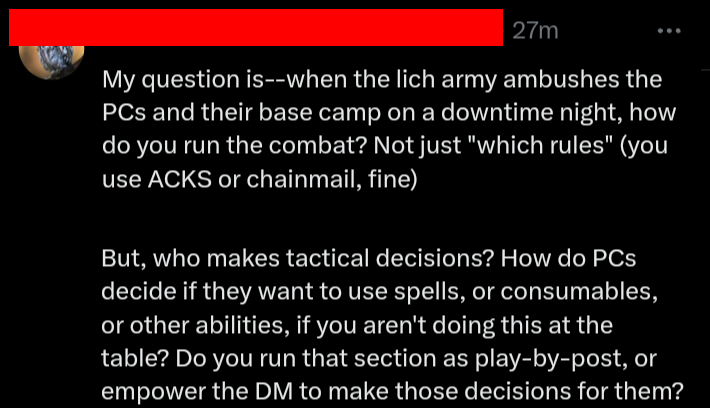

Let’s take a look at one doubting Thomas:

He is locked into the idea of “one party uber alles”, and so cannot imagine a scenario outside that understanding.

The guys playing D&D the way it was meant to be played cannot answer this hypothetical situation without asking a lot of penetrating questions first. Not because we don’t understand how conventional play works, but because we’ve been playing authentic D&D for so long that this hypothetical reads like nonsense. Here is a short list of information needed before we can formulate a response:

- What do you mean “the PCs”? Which group of PCs are we talking about?

- Who is running the lich faction?

- Who is the DM who is running this encounter, and does he have any characters involved?

- Why didn’t the PCs already make those tactical decisions when they set up camp within striking distance of the lich’s lair? What instructions did they leave the DM for such an eventuality?

- Don’t you have a phone or a text or a Discord server to handle quick questions during downtime?

- Who cares if one of the multiple parties gets wiped off-screen while running a long-term assault on a megadungeon? Don’t you have three other players ready to go?

- Wait, the lich who has been holed up in the megadungeon can be lured out of his bolt-hole that easily? I gotta get the band back together, because we can hit him when he’s vulnerable.

- Wait, the lich who has been holed up in the megadungeon can be lured out of his bolt-hole that easily? I gotta find out when the next party hits him so I can sneak in while he’s out and rifle through his hoard.

- who has been holed up in the megadungeon can be lured out of his bolt-hole that easily? I gotta…well, you get the idea.

Long story short – this hypothetical isn’t a recipe for disaster. It’s the stuff that real campaigns are made out of, and it happens more often than you think. It’s a regularly occurring feature of the real campaign.

I can’t tell you what happens because “what happens” is you playing the game. If you let the game work, if you really want to experience the best that D&D has to offer, then you and your table will come up with answers better than anything I can offer.

But there are a couple of important things to emphasize here that can sometimes go unmentioned in these discussions.

- This is a campaign management tool, meant to support neutral play by the use of a truly impartial resource. Time waits for no man, so every player gets the same number of days to scheme and implement and act. Every player gets one day of activity for every day that passes in the real world.

- This is a tool meant to maximize player agency to the greatest extent possible. The future is a great and infinite collection of potential events, which only coalesces into specific events once the players on the stage interact with that formless void. Once they do, the story is told and your agency to influence that moment is ended, lest you deny your fellow player his agency by attempting to write a paradox that negates his play.

As to the latter, we most often look forward into the formless potential. The past is written, so players have the greatest freedom of movement by looking into the future. This is a powerful play because, by moving forward in time, you are “locking out” that area and timespan from interference.

Usually.

Sometimes, though, we do look backward – in a manner of speaking. In the hypothetical posted above, the DM might reach out to the players and say, “the lich and his army hit your camp two days before the next session. Do you want to play that out in the next session?”

This is not so different from the “time jail” thrown up as a halo around future actions. The DM is reserving the megadungeon and the lich attack on the camp, preserving it from outside influence, until the gang can get back to the table. That little slice of the campaign world will hover in a state of uncertainty for the few days it takes for the resolution to play out. Once that event is resolved, you’ll have to – scratch that, everyone will want to – make sure that slice of campaign ‘catches back up’ to the rest of the campaign (read: real world calendar). You’ve got other parties out there with a stake in things to think about after all.

This happened most notably when Minas Mandalf almost got nuked. The launch codes were initiated and the big red button pushed during a session, and no one was sure what defenses the city had in place to stop it. For several days, dozens of players held their collective breath awaiting the outcome. Teh single most powerful city on the map was essentially time-locked until the situation was resolved. It was great. Every campaign should have moments with that much suspense. And yours could have it to, if you just embrace one little change. And all the dominoes that fall over after you make that little change too.

Ultimately, the question, “But what happens if,” is the best question of all.

When you answer that question, you’re playing the game.

And it’s really strange that so many people want the BROSR to play it for them.